Visualising Venus

Maxwell Montes and Lakshmi Plateau on Ishtar Terra, Venus detail(2026)

oil on canvas

Written February 2024 by Sarah E Shaw

Over the course of a year, I have immersed myself in the study of Venus, uniting the rich art historical context of the ancient Roman goddess, with scientific studies the planet’s unique features and inhospitable conditions.

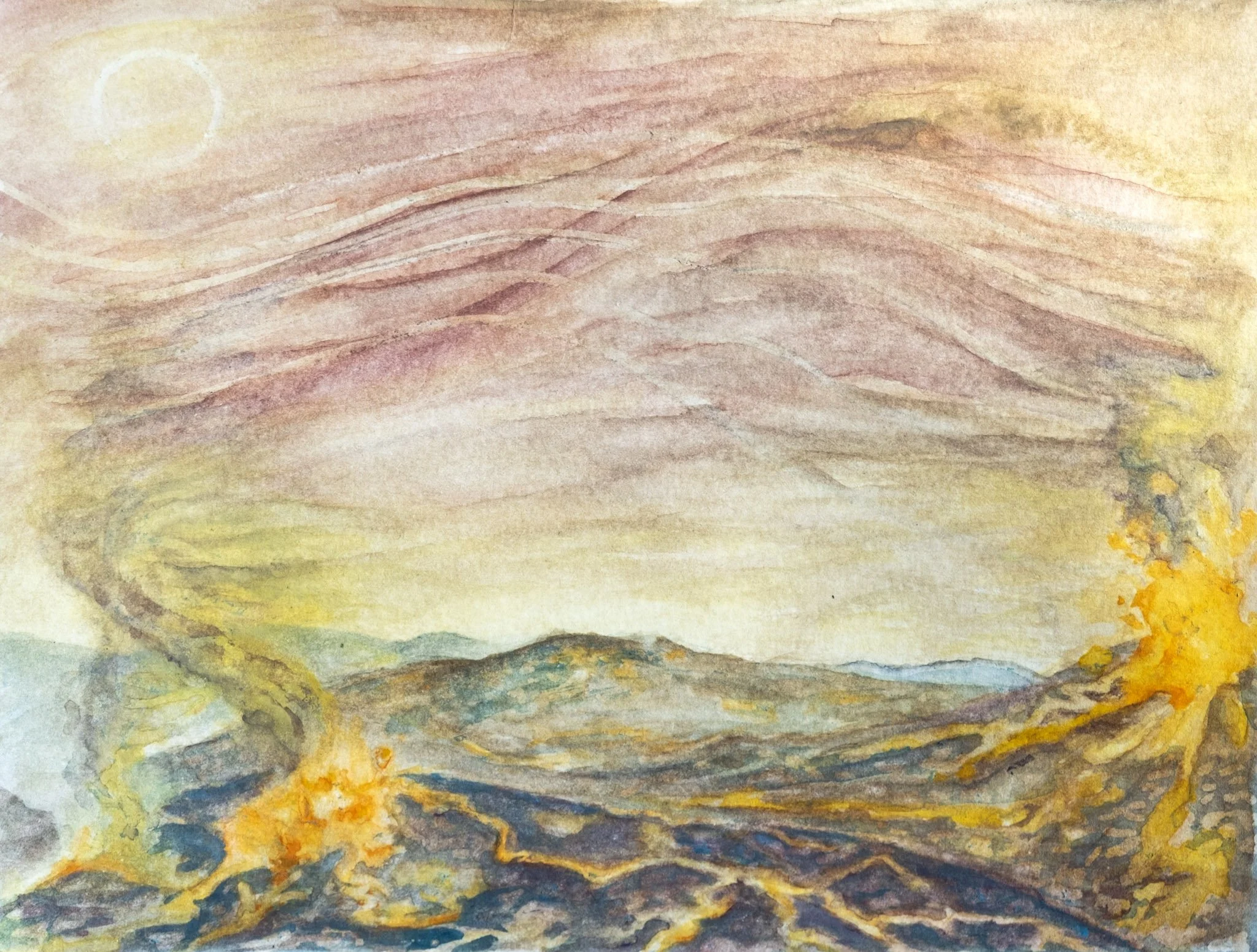

Venus IV (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

Venus III (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

Why Venus?

Venus, the only planet in our Solar System named after a female deity, embodies themes of love and beauty in mythology, captivates artists throughout art history with her nude form, and shines as the third brightest object in the sky after the Sun and Moon.

My personal fascination with Venus was almost accidental; I can’t recall exactly how or when my interest turned to this subject, but investigating its mysteries opened realms of possibilities. Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty, is a figure who has been highly celebrated in artistic depictions for many centuries, but there has been a notable absence of representation of Venus as a planet. By painting landscapes of Venus, the planet, I am seeking to redress this disparity. However, the aim was not to abandon the goddess altogether, but rather to unify her mythological essence with the harsh reality of the planet’s hostile environment, transforming it into a tranquil and sublime landscape captured through delicate layers of watercolour.

The fantasy novels I have encountered have speculated about life on the surface of the planet, whilst spiritual associations utilise movements of Venus to comprehend the forces governing the fate of our worlds. The sheer breadth of stimuli drove me to explore what responses I could offer as a visual artist

Through immersing myself in everything associated with Venus, I aim to intertwine ethereal notions of beauty and femininity with the history of our closest planetary neighbour as we understand it today. Inspecting the scientific research detailing the qualities of its layered atmosphere, the seismic activity at its surface, and its unique geological features, has deepened my curiosity and allowed me to interpret these findings through paint. Throughout this journey of discovery, I wondered how British landscape painters of the Romantic era, such as JMW Turner and John Martin, might respond to the same subject matter, so I have used some of their paintings of Earth to provide some inspiration for the composition of Venus.

Venus VII (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

Who is Venus?

While my background isn't in science but rather in art history, I've noticed a recurring fascination with Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, in the art world since the Renaissance.

A glance at prestigious art collections reveals Venus as a popular subject, far surpassing other planet namesakes. For example, a quick search in the collection of the National gallery will result in 36 hits for Mercury, 19 for Mars, 33 for Jupiter, 5 for Saturn, 0 for Uranus, 11 for Neptune and 3 for Pluto (as of February 2026). Would you like to guess how many hits for Venus?

79 for Venus.

If we go back to the Renaissance, where Botticelli's Birth of Venus in the 1480s and Titian's Venus of Urbino about 50 years later ignited a resurgence of interest in the goddess. These paintings, referenced by iconic artists like Modigliani, Manet, Goya, and Ingres, have become some of the most valuable artworks globally, with Modigliani's Nu Couché valued at $210 million USD.

So if you want to make a valuable painting, just paint Venus, preferably nude. Long-dead artists also make much better sales too…

But the subject of Venus isn’t without controversy; The toilet of Venus by Velasquez (known also as the Rokeby Venus) has attracted much attention from protesters including suffragette Mary Richardson in 1914, stating: ‘Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas.’ And most recently it has been the target of Just Stop Oil protests.

So Venus has a high stake in cultural importance, spanning many centuries. But what about her links to our planetary neighbour? How did it come to be named Venus?

The planet was observed long before the Italian renaissance by the Babylonians in about 3000BCE who knew the planet as Ishtar – the goddess of war and love. It’s not surprising that this planet has captivated the interest of many ancient civilisations since it is the third brightest body in the sky, after the sun and moon. But the ancient Roman’s deemed it appropriate to name this celestial body after the goddess of love and beauty. It is not easy to track exactly how this came about, but in Virgil’s epic poem Aeneid, Venus as the mother of Aeneis takes on a supportive and guiding role for her son whose actions are instrumental for the fate of the Roman empire. Thus, this bright object in the sky could be acting as a motherly guiding light.

Venus Victrix - Sculpture by Holme Cardwell in Manchester Art Gallery.

Venus Victrix, or Venus Victorious, holds the Apple of discord after being named ‘the fairest one’ by Paris, a precursory event to the Trojan War.

The Crouching Venus, once owned by artist Peter Lely, on display in the Dulwich Picture Gallery for the ‘Rubens and Women’ exhibition, 2024.

A Century of Speculation & Exploration

Leaping forward in time to the early 20th century, in science fiction literature, authors have often portrayed Venus as a lush, tropical world teeming with exotic flora and fauna. Classic works such as C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra and Ray Bradbury’s The Long Rain present imaginative visions of Venus as a planet brimming with life and mystery. The dense clouds that cover Venus have acted as a theatrical curtain, behind which anything is possible in the realm of imagination.

But since these realities have been hypothesized, there has been much scientific discovery. From the 1960s onwards, the Soviet Union launched their ‘Venera’ missions to Venus, and Nasa launched their ‘Mariner’ missions. The data picked up by the probes, orbiters and flyby missions will help us to paint a mental picture of the reality of this planet. The Magellan mission in 1990 was one of the most successful space missions in history, which helped to map about 85% of the planet’s surface using radar imagery, which I have used in my own depictions of Venus.

Venus XVIII (Ma’at Mons)

Graphite drawing 21 x 30 cm

Copied from a radar image taken during NASA’s 1989 Magellan mission

Venus VI (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

The Venus Sketchbooks

Since 20th January 2023, I have kept a Venus sketchbook, in which I could scrawl my feelings of Venus as I learnt more about it. My exploration first revealed the extreme nature of its climate, and an abundance of volcanic activity. Surface temperatures are an average of 470 degrees Celsius, making Venus the hottest planet in our Solar System. I began making abstract watercolour sketches aiming to conjure this inferno-like environment on paper.

As my exploration continued, my interest and fascination with this planet deepened. What began as a curiosity was soon to become a project I dedicated a lot of my spare time to! Eventually I was equipped with the knowledge to be able to visualise this planet in my mind, and transport myself there each time I painted. With every painting, I got a bit closer to the surface of Venus.

Venus XI (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

Venus XIII (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

JMW Turner (1775 - 1851)

Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps (ex. 1812)

Oil on Canvas 146 x 237.5 cm

Turner bequest, 1856, © Tate, Photo: Tate

Venus VII (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

A Trip to Venus

So let’s take a trip there for ourselves. The use of your imagination is encouraged as we embark on this journey. For safety and protection from the elements, we can encase ourselves in the transluscent crystal sarcophagus imagined by C.S Lewis in his novel Perelandra, for Dr Ransom’s journey to Venus.

We will lift ourselves out of wherever we are on Earth, say farewell to our comfortable and familiar planet, and voyage towards Venus. Luckily for us it’s our closest planetary neighbour, so the journey takes roughly 3.5 to 4 months.

Let’s imagine ourselves now as Japan’s Akatsuki orbiter, which is loaded with imaging technology

As we look at Venus from space, we can see the thick white clouds containing a pale yellow glow. Among these clouds, we can make out curves which appear like ‘sideways smiles’ on the planets atmosphere.

Lo and behold, Venus has curves.

The clouds that shroud Venus are rotating clockwise around the planet. This is quite strange. Venus is one of two planets in the Solar System which experiences retrograde rotation, spinning clockwise on its axis, as opposed to every other planet which rotates anticlockwise. There are two ways we can look at this, either Venus has a tilt of 3 degrees and spinning clockwise, or it has a tilt of 177 degrees (as opposed to Earth’s 23 degrees) and is spinning anticlockwise – in other words, the planet could be upside down.

But even as the white clouds are circulating Venus very quickly, about 100m/s, these sideways smiles are remaining relatively still. What’s happening beneath these clouds? Let’s get in a bit closer and find out.

Venus XVI (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

Descending toward the planet's surface, we discover this veil of clouds is composed primarily of water ice clouds and crystallised carbon dioxide. It makes for a very white and wintery scene. As we are completely immerse in these clouds, we lose sight of our home planet Earth, and diving deeper in we are beginning to lose the shape and sight of our sun. It’s like being caught in a snow storm where you can see nothing but white, and we are being hit with the solid icicles contained here. As we continue our descent, we are met with a haze of sulfuric acid which breaks up the stark white sheet with a hazy yellow orange glow.

The temperature is getting a little hotter, but comfortable. Now we are in the mesosphere, about 50km above the planet’s surface, and we are floating just above densest part of the Planet’s atmosphere. It’s here that scientist, Geoffrey Landis, has hypothesized about the potential colonisation of Venus. As breathable air will float like a helium balloon does here on Earth, humans may be able to exist in balloon-like blimps being blown around this layer of the atmosphere.

Venus XV (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

Venus XII (2023)

Watercolour

30 x 21 cm

Venus XXIII (2023)

Watercolour 30 x 22cm

But let’s not get too comfortable here, let’s push ourselves down through the troposphere, to the reach the surface of Venus. This layer contains about 99% of the atmosphere by mass. What we’ve experienced so far has been very light and easy to move through, but this next part requires a lot force to wade through it. It’s like the resistance we feel when trying to walk in a swimming pool but amplified by about 100. In fact, it’s closer to the pressure you would feel being submerged deep in the ocean on Earth.

Nevertheless, we are here now on the surface of Venus, so take some time to look around you. We are on Aphrodite Terra, the largest of three landmasses on Venus. The ground is made of rocky black/grey basalt and steeped in lava flows. The sky above us is a very hazy yellow orange. Only about 10% of the sun’s light makes it down here to the surface, so it’s similar to a very overcast day on Earth. The diffraction of the sun’s light here has some very interesting effect on the colours that we can see. Much of the blue light is absorbed by an unknown compound in the atmosphere, so everything is veiled in red and orange. It’s difficult to make accurate comparisons with what we experience back on Earth, since there are some elements of Venus that are unique only to this planet, and do not exist elsewhere in the universe – that we know of. I’m speaking of the arachonid lava flows, which form vast channels like spider’s webs on the planet’s surface. It’s possible that these flows came from one of the many volcanos here on Venus. Another explanation is that they arose from the interior of the planet. Another unique trait of Venus are its ‘Farra’ or ‘pancake domes’, which look like large round, flat volcanic craters, but they are emitting some kind of gas – probably more sulphuric dioxide.

The longer we spend here, the more we realise how inhospitable it really is on the surface. The atmospheric pressure is 93 bars, 90 times the pressure on Earth. That’s roughly 948 tons of weight per square metre. We are currently being crushed under the weight of about 7 statues of liberty, or 9 Blue Whales, per square metre. On top of that, the surface temperature averages about 460 degrees C, which is hot enough to melt lead. Venera 8, launched by the soviets in 1972 lasted less than one hour down here on Venus.

Perhaps there might be some respite from this heat as night draws in? Well, here on Venus we would have to wait approximately 117 Earth days from sunrise until sunset. Although we were observing the planet spinning quickly from outer space, it was all an illusion, created by the atmosphere which travels about 4 times as fast as the planets actual rotation. Venus takes about 243 Earth days to make one full rotation. That’s even longer than a Venus year – it takes 225 Earth days for Venus to orbit the Sun.

Maxwell Montes and Lakshmi Plateau on Ishtar Terra, Venus (2026) Oil on Canvas 61 x 97 cm

Venus XX, Maat Mons (2023)

Watercolour on Paper 60 x 42 cm

Ma’at Mons pollutes the atmosphere (Venus XXXVIII)

(2023)

Watercolour on paper

38 x 27 cm

The harsh temperature down here on Venus has very little to do with its proximity to the sun, and more to do with the greenhouse effect caused by the large proportion of carbon dioxide in this layer of the atmosphere. If we look across to Ma’at Mons, one of Venus’ large shield volcanos we can see it spewing out gases: carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide. These are polluting the atmosphere and leading to a runaway greenhouse effect. It is not known what the surface of this planet could have looked like millions of years ago, so again we are called to speculate. The hellish landscape we now see could have once had seas, continents and life much like Earth. It has been labelled as Earth’s sister planet, or Earth’s twin, due to its size and geological makeup being quite similar, but as we have seen here today, there is very little left to draw comparison on. Hopes of finding intelligent life on Venus as sci-fi novels have fantasized about in the early 20th century, have been dashed by the discovery of the planet’s reality.

President Lyndon Johnson, US president at the time of the Mariner 4 mission:

“It just may be that life on Earth as we know it is more unique than we may have thought”

Prof. Brian Cox reimagining Holst’s Planet Suite:

“Venus is the closest world to Hell you could possibly imagine.”

The greenhouse effect heated the planet up and destroyed it as a habitable world.

Planets are not eternal, a world that was once heaven can become hell. Venus, bringer of peace becomes a requiem for a failed planet and perhaps also a reflection on how rare places like Earth might be.

Venus XXXVII (2023)

Watercolour

21 x 15 cm

The Future of Venus

NASA's upcoming missions, such as the VERITAS and DAVINCI+ missions, aim to further our understanding of Venus's geological history, surface composition, and atmospheric dynamics. Additionally, private space companies, including SpaceX and Blue Origin, have expressed interest in launching missions to Venus, signalling a renaissance in Venus exploration. This renewed interest may be a result of the research of Jane Greaves, professor of astronomy at Cardiff University, as her research has revealed the possible presence of phosphines in the planet’s atmosphere, an indication of the presence of microbial life. Her team used William Herschel’s 40ft telescope located in the Canary Islands to observe the atmosphere of Venus. So we could be very close to discovering life on another planet in our solar system. Later this year, Rocket lab and MIT will launch a relatively low-cost mission to Venus ($10 million USD) to study part of its atmosphere. The mission is aptly named ‘Life Finder’

Venus XLII

(2023)

Watercolour on paper

53 x 43 cm